Michael Schrage’s book, Serious Play: How The World’s Best Companies Simulate to Innovate to Win, is worth a read as a general business book, but also very applicable to supply chain network design.

The book is about the prototypes an organization builds to help make decisions. And, a network design model is a prototype of the supply chain. So, many of the lessons apply directly to the supply chain team. And, when you read the book, it makes you wonder why a company wouldn’t want a model of their supply chain.

One of his key insights breaks a myth that it is a good team that creates a good prototype. Instead, he argues that it is a good prototype that creates the good team and leads to discussion and insight. He goes further to say that what is interesting about prototypes is not the model themselves, but what the models teach us about the organization.

Using a network design model as an example, he would ask questions like who gets to build the model, who gets to see the model, who gets to make suggestions, when do people get to see the model, do customers get to see the model, or do suppliers? All these are good questions for a team building a supply chain model.

The book is full of different ideas you can apply to your modeling efforts. Here are a few I pulled out:

- “Waste as Thrift” (pg 100-101). Once you have a model in place, it is relatively inexpensive to test ideas. If you don’t “waste” scenarios, you are really risking wasting real money when you implement an idea without testing it.

- “Bigger Isn’t Better (pg 131-137). The object of the prototype or model isn’t to be as complex as reality. Instead, the model needs to be understood by those who need to make decisions.

- “The act of designing the model…is essential to understanding their use” (pg 168). He argues that their is value in putting the model together. We see this as well and think it is well worth your time to understand some of the underlying math.

- It is important to create “conflict” with the model (pg 173). The “conflict” is to set up the model to expose important trade-offs like cost versus service. In network design, multi-objective optimization is great at bringing out those trade-offs.

- “A prototype should be an invitation to play” (pg 208). A great way to get value from a model is to play with it try new things and see if you can come with some counter-intuitive solutions that change everyone’s thinking.

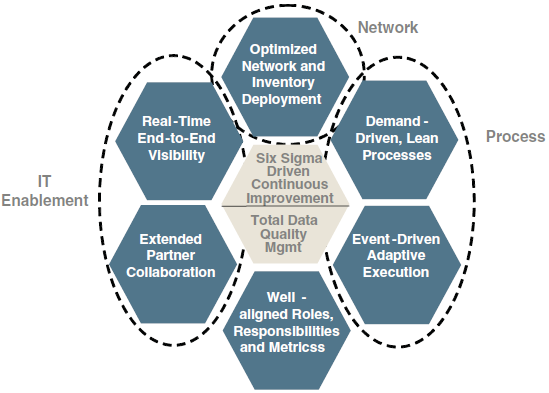

PRTM (now part of PwC) and LogicTools (now part of IBM) published a white paper showing how firms create efficient supply chains:

PRTM (now part of PwC) and LogicTools (now part of IBM) published a white paper showing how firms create efficient supply chains: